This is a Google translated version.

In the Dutch Journal of Medicine (NTvG) is an article published by Huijbregts et al. It is about cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), or as they refer to ME / CFS. It is being investigated whether this could be an effective treatment for patients with long-term complaints after a covid-19 infection. This is because we know from previous epidemics that some of the patients do not fully recover after an infection and that they are CVS criteria. They also argue for an amended Health Council recommendation to avoid confusion. I agree that the report should be amended for other reasons, but have Huijbregts et al. Achieved the intended reduction in confusion with this article?

Firstly, the symptoms are discussed and that is where things actually go wrong. They refer to the description on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. This is based on the Institute of Medicine report 2015.

The descriptions of the other symptoms are correct, except for the difficult recovery after exercise. As the CDC website describes, patients experience a worsening after physical or mental exertion called post-exertional malaise (PEM). That is different from mere painstaking recovery.

The 2015 Institute of Medicine report (the US Health Council) spoke of the “hallmark symptom” and the name Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease was suggested. Slow recovery is not actually the problem, it is getting sicker (not tired) after a (little) effort. Given that PEM is the most recognizable symptom of the condition, I also wonder why it is not explicitly mentioned. By only mentioning difficult recovery, but not getting sicker after exercise, this only creates confusion.

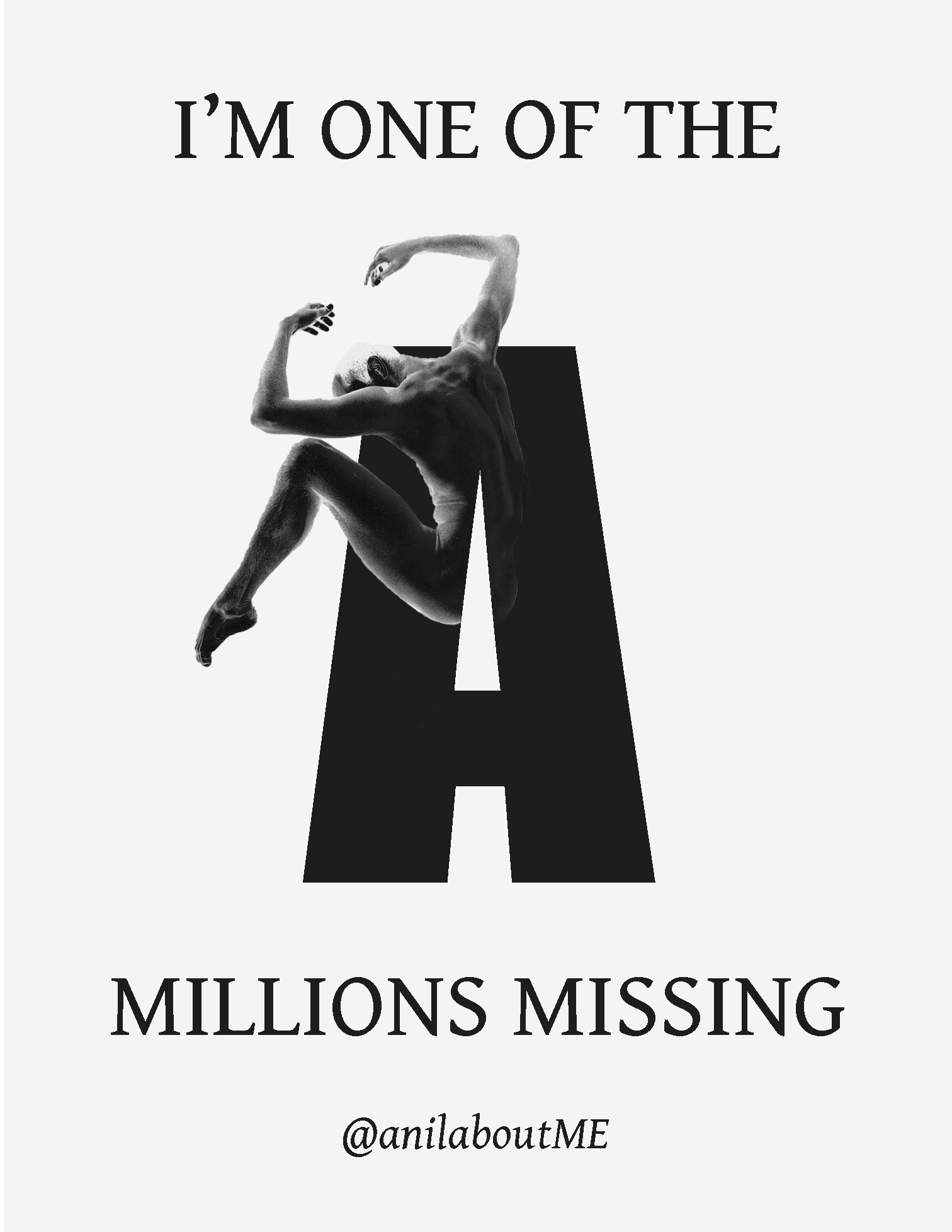

The authors also indicate that six months of fatigue could lead to a diagnosis of ME / CFS. I myself always refer to ME. I cannot agree with the name / acronym CFS as this suggests that the condition consists mainly of chronic fatigue. This while my most disabling complaints are PEM and Orthostatic Intolerance (OI). I’m bedbound by the OI. I am never actually talking about fatigue, but about being sick. It feels like a kind of chronic flu. In terms of disability, that flu-like exhaustion is in sixth place of my complaints. Curiously, Huijbregts et al. Omit OI entirely, even though it is listed on the CDC website for one of the additional symptoms needed. Scientists have been in multiple studies here, and here, suggested that PEM and OI are linked.

Fatigue is not even a criterion for the International Consensus Criteria. Because the authors highlight fatigue as the symptom of the condition and omit OI, they again cause unnecessary confusion.

CBT / GET effective?

Using the NICE 2007 guidelines and the Cochrane reviews for CBT and GET, the authors say these treatments, although moderately, have been shown to be effective.

However, according to one review by Vink et al. the CBT Cochrane review is based purely on subjective measures that do not match the disappointing objective measures. These show no significant or no progress. Most of the studies in the Cochrane review did not report any safety or side effects. Patient data indicate unfavorable results in 20 percent of the cases. Vink et al. Indicate that the dropout / missing data rate was high in a number of studies and these losses are unlikely to be random.

In a another review by Vink et al. they analyze the Cochrane GET review. Subjective measures there too. Objectives showed that GET is not effective. Also more dropouts in the treatment groups than in the control groups.

- Wearden et al. (1998) dropped out 37.3 percent in the two GET groups combined, but only 21.7 percent in the two control groups combined.

- In Powell et al. (2001), 18 percent dropped out in the GET groups compared to only 5.9 percent in the control group.

- In Moss-Morris et al. (2005) this was 12 and 0 percent respectively. “

Furthermore, there were poorly matched control groups, relying on an unreliable fatigue tool as the primary outcome, switching outcomes, p-hacking, ignoring evidence of damage, etc.

That doesn’t sound very encouraging.

PACE trial.

Indeed, there is much controversy surrounding the PACE trial. The now infamous PACE study, which was the largest study ever done on “CFS”. The model that was used states that after an infection you started doing less physical activity. The disease is perpetuated by false or unhelpful views about being sick. In other words, you are no longer sick and patients can recover or be cured if they can overcome their fear of activity. All PEM symptoms are just normal body responses because your condition has deteriorated, not a sign that you are making it worse. This is an unproven hypothesis and the basis for it many such clinical trials.

The PACE study, and a similar study such as FITNET, tried to convince people to overcome their “fear” of activity. The subjective outcome measures showed some temporary subjective improvements after post-hoc manipulation of the data. Nevertheless, the improvements in the objective outcome measures were not significant and did not match the subjective ones.

After a struggle of 5 years, the authors of the PACE study were forced by court order to release the raw data from this controversial study. The publication of the original report in The Lancet stated that 60% of the patients improved and 20% recovered. However, after a reanalysis with the original protocol, it appeared that only 20% patients improved and that only 7% recovered.

Huijbregts et al. Indicate that “after reanalysis of these data , patients pointed out that not everyone benefits from CBT.” But why are only patients referred to?

The lead author of the reanalysis of the PACE trial is psychologist Carolyn Wilshire, PhD, Senior Lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington

Further co-authors are:

- David Tuller DrPH is a Senior Fellow in Public Health in Journalism at the Center of Global Public Health, School of Public Health at Berkeley University

- Professor of Biostatistics Bruce Levin of Columbia University.

- Dr Keith Geraghty MPH, PhD Manchester University.

- With additional three “citizen scientists” and patients Tom Kindlon, Alem Matthees and Robert Courtney.

Interestingly, the reanalysis is not directly referred to, but rather a response from Wilshire and Kindlon to the PACE trial authors. That paints a distorted picture.

An open letter was issued after the reanalysis more than 100 scientists and practitioners, ten members of the House of Commons and several patient organizations. An independent re-analysis of the study data at an individual level was requested. So these are not only patients. Then why does the article refer to only dissatisfied patients? How incredibly misleading!

No damage.

According to Huijbregts et al. Research shows that CBT does not cause iatrogenic damage. They refer to a study from 2010. They conclude that on the basis of the data CBT, although it was not statistically significant, performed better than the control group. Given that the control group also deteriorated, the deterioration could not be attributed to CBT.

However, they forget to mention one important part. One of the studies was also included in the Cochrane review. This study by Prins et al. 2001 showed a dropout rate of 40.9 percent (CBT) and 23.1 percent (no treatment). This is in line with the trend seen in other CBT / GET studies in the Cochrane reviews. Like it Addendum 2016 of the Agency Research Healthcare and Quality indicates that the harmful consequences are strangely badly reported.

However, they forget to mention one important part. One of the studies was also included in the Cochrane review. This study by Prins et al. 2001 showed a dropout rate of 40.9 percent (CBT) and 23.1 percent (no treatment). This is in line with the trend seen in other CBT / GET studies in the Cochrane reviews. Like it Addendum 2016 of the Agency Research Healthcare and Quality indicates that the harmful consequences are strangely badly reported.

If you do not include those results, a more positive CBT result is not surprising. However, there are some indications for this direct and indirect negative consequences of CBT and GET to be found in the scientific literature. For example, an increasing claim on disability benefits, shorter working hours, low compliance and thus more dropout in the treatment arm than in the control group. I am therefore concerned that the authors’ conclusions on safety are incorrect. This again creates additional confusion.

Despite the fact that Huijbregts et al. Find it difficult to understand that the Health Council of 2018 came to the conclusion in its advisory report that ‘CBT cannot be regarded as an adequate treatment to which patients can be obliged according to medical standards’, that decision has nothing to do with the pressure on patients, but all with the fact that the scientific literature showed and shows little impressive. In fact, it is extremely disappointing.

I agree that GET and CBT are not the same treatments. However, the distinction between who does or does not respond well to GET does not lie with those who are naturally inclined to overload themselves. The difference is whether you have post-exertional malaise or not. For criteria for the CBT / GET studies, PEM is optional or not required at all. These studies do not necessarily say anything about patients with PEM. This is also indicated to a greater or lesser extent by the AHRQ Addendum 2016 (Oxford criteria) and the Cochrane GET review 2019 (Oxford and Fukuda criteria).

Because of PEM, CBT with a GET component or GET is simply contra-indicated. Plain and simple.

NICE is nice or not so nice?

The article avoids a very large “elephant in the room”. Reference is made to the NICE guidelines 2007 and to the 2020 warning for GET at LongCovid. This indicates that the NICE guidelines for ME are being revised. What the piece avoids mentioning completely is that the concept of the NICE guidelines 2020 is already in November 2020 is published. The fact that they do not mention this is perhaps not so strange because the conclusions are not tender.

“Only offer cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to people with ME / CFS who would like to use it to support them in managing their symptoms of ME / CFS and to reduce the psychological distress associated with having a chronic illness. Do not offer CBT as a treatment or cure for ME / CFS. ” (Section 1.11.43).

“Do not offer people with ME / CFS: any therapy based on physical activity or exercise as a treatment or cure for ME / CFS; generalized physical activity or exercise programs – this includes programs developed for healthy people or people with other illnesses; any program based on fixed incremental increases in physical activity or exercise, for example graded exercise therapy… ” (Section 1.11.16)

But not only that. Here are the ratings of the CBT and GET outcomes by NICE Analyzed by Psychology Professor Brian Hughes:

– Of the CBT studies, NICE rated the evidence for 89% of the 172 outcomes as VERY LOW and 11% as LOW.

– Of the GET studies, NICE rated the evidence for 81% of the 64 outcomes as VERY LOW and 19% as LOW.

None of the outcomes were found to be higher than low. 9 of the studies came from the Netherlands. One of the studies by Knoop et al. 2008 was part of the 2010 review mentioned by Huijbregts et al. That should prove safety.

Thus, the quality of the outcomes for this study was for the most part of VERY LOW evidence, according to NICE. In view of the study by Prins et al. With high drop-outs and Knoop et al. 2008 with poor ratings by NICE, the 2010 study on safety can be thrown straight away in my opinion.

PACEing

What is special is that the authors still mention adaptive pacing at the end. Although there is a difference between adaptive pacing and pacing , their approach seems symptom contingent. Within boundaries. No graded activity or graded exercise therapy. This is also what the CDC, Health Council 2018 and the draft NICE guidelines 2020 recommend. Within the “energy envelope” as the most important part of learning to deal with the disease and especially PEM.

Pacing is not, as Huijbregts et al believe, only suitable for those who want to achieve the old level at all costs. Pacing is for anyone suffering from this condition. This simply has to do with whether someone meets the CFS criteria with optional, and therefore without, PEM versus ME or ME / CFS criteria with PEM. It is also for that reason that the CDC, Health Council 2018 and the draft NICE guidelines 2020 have made PEM a mandatory symptom. This is to avoid confusion and iatrogenic damage. Plain and simple again. The authors do not make this distinction. Refer to studies that do not make this distinction and therefore cause even more unnecessary confusion.

I agree with the authors that the Health Council of 2018 has failed both CBT and the patient. Because of the four CBT advocates in the Health Council, the report is still problematic in this respect because it has not distanced itself from this unhelpful form of CBT. The concept of the NICE guidelines 2020 has clearly done that a lot better.

I could have imagined it somewhat if the authors had not deviated so extensively about the concept of the NICE guidelines. It is also “just” a concept and we have yet to see what the final result will be. But not to mention it at all is very special. On the other hand, it is not entirely surprising as it significantly undermines their argument. It possibly also explains the timing just before the planned publication in April 2021?

The good news is that the Zorginstituut in the Netherlands has already indicated that they are going to see if they have the Be able to adopt NICE guidelines in their entirety. Even if this does not succeed in its entirety, the NICE guidelines will also cause quite a few changes here.

Next!

Huijbregts et al. Come up with a new recommendation text for an amended Health Council, but given the latest scientific knowledge, I am afraid that this will never happen. I do agree that a patient should always choose a treatment themselves. But on the basis of this article, despite this being the criterion according to the authors, patients will definitely not be sufficiently informed about this form of treatment. Both practitioners and patients have been misled and that is extremely worrying.

To be clear, I am absolutely for psychological support. I look forward to the day where patients can confidently turn to a psychiatrist or psychologist and tell his or her story because the practitioner is fully aware of what this disease entails. To date, this is generally not the case and often still leads to iatrogenic damage.

Huijbregts et al. Aimed to reduce confusion, but in my view they clearly failed to do so. Many therapists and patients who have been misled by spreading the misinformation. This does not contribute to the progression. We need psychologists who are not afraid to speak out against the current paradigm. Psychologists who want to work with the patient community to develop better treatments. Treatments that match the patient’s experience. Huijbregts et al. Devalidate this experience by adhering to this form of CBT / GET. They are clearly not part of the solution, but rather of the problem. This is of no use to us as patients. It is a waste of wasted time, money, but especially the lives that are already so neglected. We patients have no time to waste, so with other words… next !!!