WRITE WITH US

Last week three articles about infection-associated chronic illnesses (IACI) were published. One in a newspaper by a doctor who had attended a refresher course on IACI, one in the Dutch Journal of Medicine, and one in Medisch Contact by a doctor in response to the IACI protest that took place on November 30 at the Malieveld, and the question of why we hear so little from the medical and scientific world.

The first two articles received a lot of criticism because what was written did not align with the experiences of patients. Moreover, scientific insights and current knowledge were misinterpreted and miscommunicated. Behavioral interventions that over the years have proven ineffective and harmful, and from which there is increasing international distancing, were presented as positive. In both articles, as we unfortunately are used to, there was once again unnecessary psychologizing.

The piece in Medisch Contact, on the other hand, was received with applause because it fully reflected the current situation regarding the lack of care for patients, the lack of involvement and motivation within a significant part of the medical and scientific world to bring about change.

The difference is that the last piece was written by a doctor who himself is affected by a IACI. In the first two pieces this was, as far as I know, not the case. The difference in how pieces then align with what is known about IACI both scientifically and in validating the experiences of patients is considerable.

A GAP IN KNOWLEDGE?

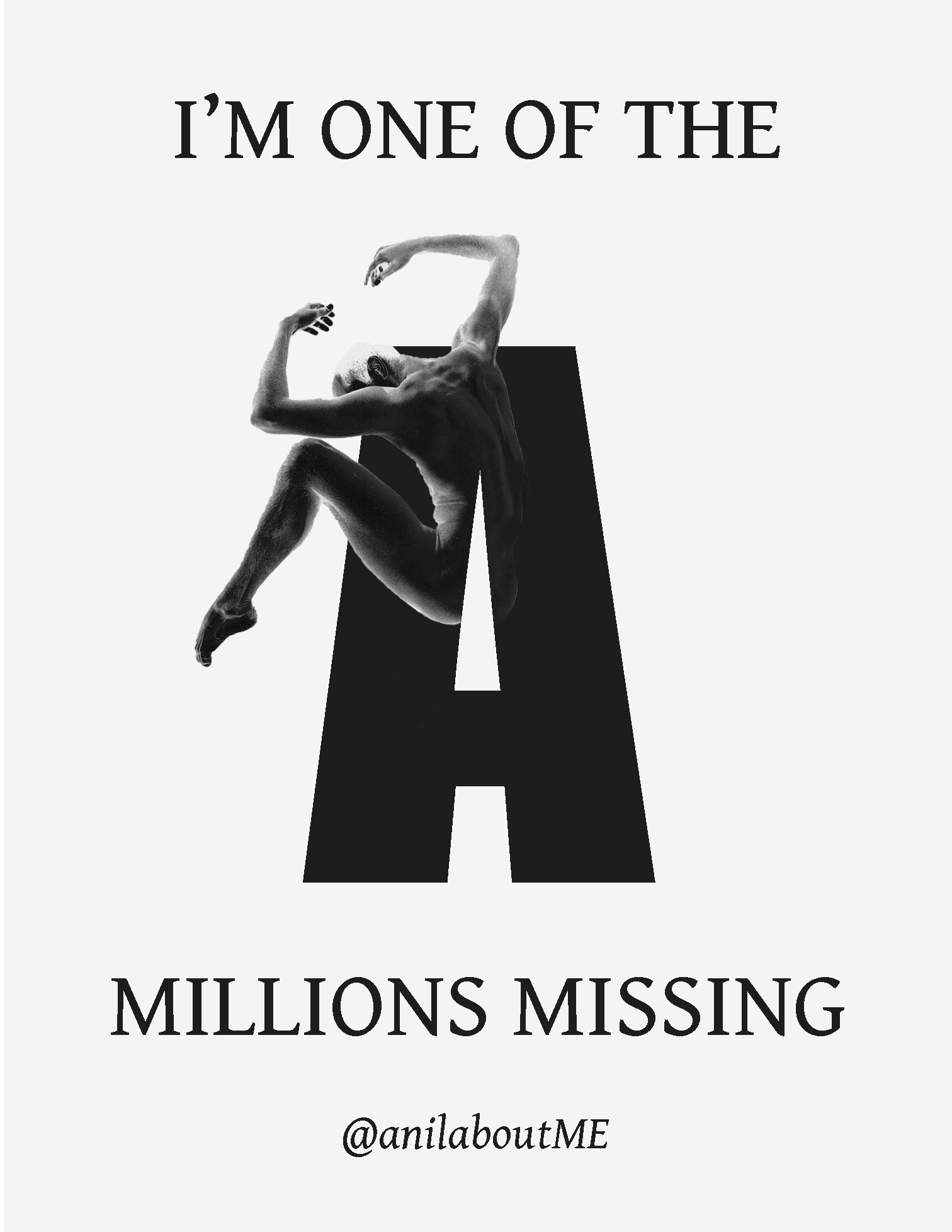

This problem has existed for decades: a separation between the academic or medical world and the patient community. Those who studied for it versus those who are ill and have little formal knowledge. Because let’s be honest, in my case, what does a former ballet dancer know about the underlying pathophysiology? It is a textbook example of epistemic injustice: the structural underestimation of experiential knowledge compared to formal academic knowledge.

We patients are of course the ones who experience the disease daily. We know better than anyone how it feels to live with such a disease. Moreover, unlike many doctors and scientists, patients only have to concentrate on one disease profile at a time. Every scientific publication is critically evaluated in various places on the internet. My personal knowledge is therefore admittedly one-sided, but in this way I have still built up a lot of basic knowledge.

Although this was already the case before the pandemic, since then a significant number of doctors and scientists have themselves developed a IACI. The separation between the patient community and the practicing medical and scientific world has therefore become smaller. In fact, their academic and medical expertise transcends for me that traditional separation.

SIGN OF STRENGHT

In my view there is therefore no longer any excuse not to work closely with the patient community. Over the years I have often been approached by doctors and scientists to help correct or collaborate on articles, blogs, podcasts, or whatever. And it is precisely these doctors, scientists, or other healthcare professionals who attach great value to the knowledge of patients whose story best corresponds with the latest state of international scientific developments, appropriate care, and the experiences of patients.

We see this internationally too, and with Long Covid. It was not the work of researchers from before the pandemic, which did not sufficiently align with the experiences of patients because they communicated too little or not at all with us, and therefore propagated a wrong narrative about IACI, that contributed to the wrong knowledge and understanding. The right insights about IACI came from researchers and doctors from before the pandemic who did work intensively with patients. It was precisely this collaboration that in the early phase of Long Covid contributed to the clinical disease profile being better understood and relevant knowledge and guidance becoming available more quickly. Often these are also scientists and doctors who out of necessity delved into IACI because they themselves, a family member, or a friend was affected by IACI.

The right understanding is not only beneficial for science and care, but also contributes to cost-effectiveness. Promoting ineffective interventions leads to waste of resources, worsening of disability, and higher healthcare costs. That is counterproductive and far from rational.

One must realize that it is not a weakness to verify information with experts by experience; on the contrary, it is an essential step in quality assurance.

COLLABORATION IS THE FUTURE

For the Dutch ZonMw biomedical research program for ME, patient participation is also a requirement. That may take some getting used to for everyone, and certainly for scientists. It may initially even cause some delay, but in the long term it pays off. We saw this also during the HIV/AIDS crisis, where the voice of experts by experience was essential for both correct understanding and scientific progress.

I think this should also be the standard for publications about IACI. For a scientific journal there should not only be peer review by other scientists, but also structural involvement of experienced citizen scientists. Many of the mistakes I see concern elementary knowledge. I am astonished how such mistakes even get through peer review. There should be no room for alternative facts and misinformation in the scientific literature. Yet it happens, even in leading journals.

For opinion pieces in newspapers or other platforms the situation is partly different, but even there consultation with patient organizations or other experts by experience could prevent a lot of misinformation. Especially with diseases that are harder to objectify, the experience of patients is essential for correct understanding, for stimulating relevant science, and for care that matches the disease profile.

Unfortunately, that was exactly what was lacking this past week and that is simply unnecessary.

It is simple. No participation means no legitimacy.

So do not write about us, but with us.

Do not research, develop, and decide anything about us, but with us.

Nothing about us without us.

Nothing about M.E. without M.E.

Thank you!