The honeymoon.

Before becoming ill, my relationship with the medical world was always great. It was pretty much straightforward really.

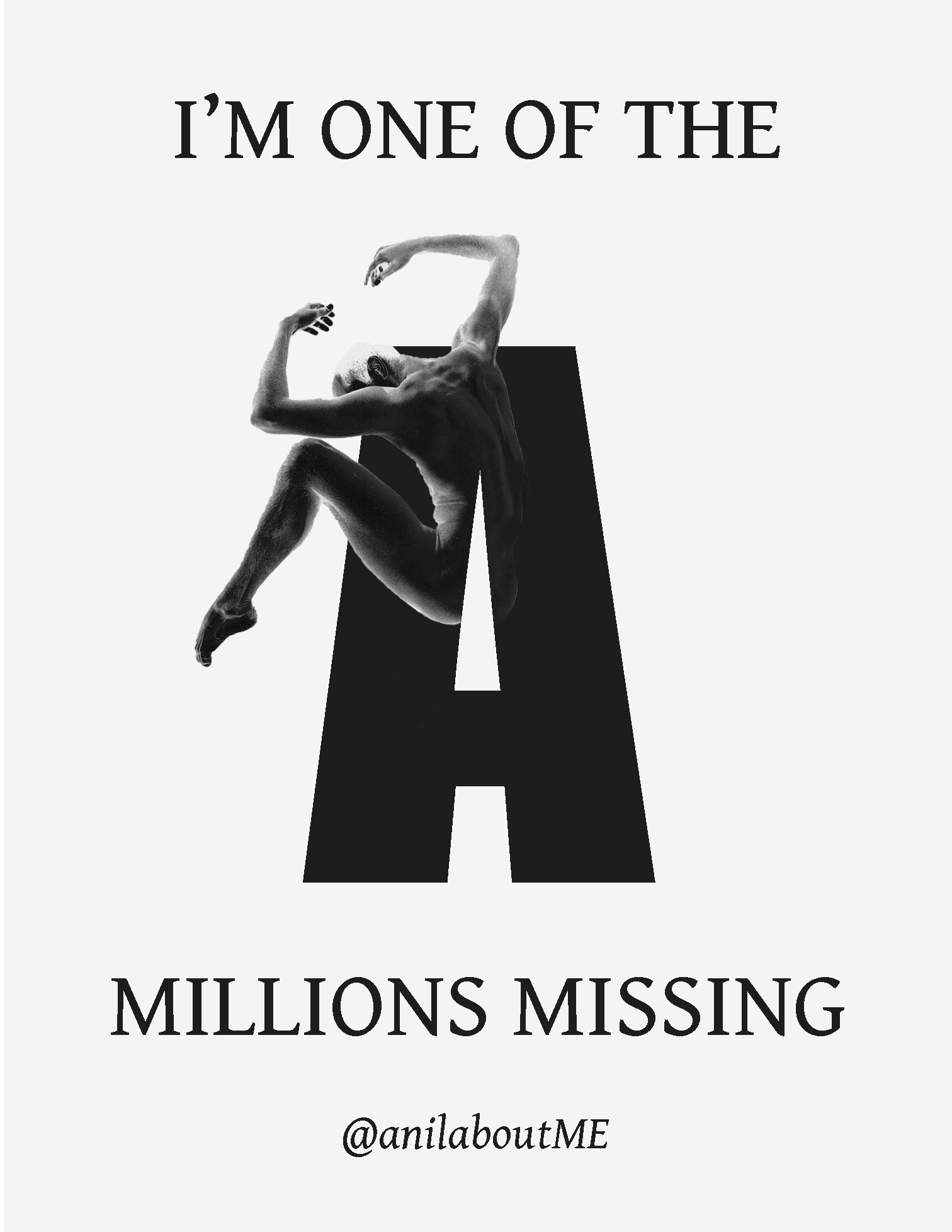

During my profession as a dancer, injuries were of course always of a concern. I had to be in close contact with doctors, physiotherapists, massage therapists, chiropractors. The only way was up. Back to full health and recovery. I was considered a reliable dancer with a focus on “the show must go on” and a patient with great resilience.

When I contracted a cytomegaloviral infection and didn’t seem to be recovering, that all came to a squeaking halt. I tried all the go-to treatments like graded exercise therapy (GET) which didn’t really seem to work. In fact the building up of my activity levels made me significantly worse!

I suddenly became a patient that nobody knew how to really treat anymore. Walking into the office of my doctor had a whole different feel to it. From the “all smiles there’s Anil”. To “Oh gosh there’s Anil”. There was a certain fear in my doctor’s eyes!

I suddenly became a patient that nobody knew how to really treat anymore. Walking into the office of my doctor had a whole different feel to it. From the “all smiles there’s Anil”. To “Oh gosh there’s Anil”. There was a certain fear in my doctor’s eyes!

At the time I wasn’t really aware that patients with a disease like ME could be considered “difficult” patients. Not only because of the fact that they might be hard to treat, but difficult as a person. All kinds of character traits have been assigned to patients that suffer from diseases like ME.

For example, a lack of resilience to deal with symptoms and that they’re doctor shoppers with or without the intention of secondary gains. Some even talk about us as being needy and even hateful. It’s not uncommon when you mention the fact that you have ME, that the treatment you’re going to get will change in an instant.

Now luckily this is not the case with every practitioner and I do think things are slowly changing. That being said I’ve always wondered how it got to this point in the first place. Why do some practitioners almost seem to hate their patients. Are these really the characteristics of patients with a disease like ME? Is this exclusively for a disease like ME? Are there likely ways to improve communication?

The treatment.

One of the biggest issues is the treatment of ME. There aren’t any FDA approved treatments for ME. The only “proven’ and “preferential” treatments are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and GET. According to psychiatry, these treatments have the ability to even cure patients from their chronic fatigue (CF).

The CBT/GET model suggests that after an initial infection you will have physically started doing less. The disease is then said to be caused by false or unhelpful illness beliefs about the patient having a somatic illness. In other words, you are said to be no longer ill and that patients can recover if they are able to overcome their fear of activities and that any worsening after exertion is just a normal reaction of the body because you’re deconditioned. It’s not a sign that you’re making things worse.

The core symptom of the illness is not “fatigue” but the relapses which patients suffer from after over-exerting themselves, often referred to as post exertional malaise (PEM), which makes CBT/GET clearly contra-indicated as a treatments.

CBT is used in various diseases, but when applied to multiple sclerosis, diabetes or rheumatism, CBT does not claim to be a cure. By reducing the disease, ME, to just fatigue, they project the image of having a cure for the disease itself. That is not the case. Fatigue is just a symptom of many diseases. It’s not a disease in itself.

CBT is used in various diseases, but when applied to multiple sclerosis, diabetes or rheumatism, CBT does not claim to be a cure. By reducing the disease, ME, to just fatigue, they project the image of having a cure for the disease itself. That is not the case. Fatigue is just a symptom of many diseases. It’s not a disease in itself.

Now besides the fact that the model doesn’t fit with the disease mechanism of ME and the methodological flaws of these trials are even more astonishing, many patients are aware of these issues in regards to the behavioral science, but what about the medical world? If you step into a doctor’s office it’s not unlikely that doctors will suggest trying CBT and GET.

One of my GPs in the Netherlands suggested that I should try CBT although I already explained to her that CBT (with a GET component) made me significantly worse. Her argument was that CBT has also shown to be effective in cancer. I wasn’t as aware of the science behind the CBT/GET trials at the time so I kind of let that comment slide but when looking back it clearly showed that she wasn’t aware of the flawed rationale behind the science.

Regardless of the fact that the treatments made me worse because of the PEM, she still recommended it. The question is, could I really blame her for not not knowing?

Doctors just simply don’t really have the time to read through all the latest and greatest news of every single disease. They need clear information filtered down through clinical guidelines or recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Cochrane or wherever, assuming the information is sound.

Confusing.

If you look for instance at the information in the Netherlands on websites such as the Dutch Knowledge Center for Chronic Fatigue (NKCV), they claim that chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is not a chronic condition and that CFS can be fully recovered from.

“Fear false evidence appearing real.”

Their studies also claim to show that CBT doesn’t cause harm. So maybe they’re just talking about CFS and not ME? Apparently not. The NKCV feels that ME and CFS are the same and that, apparently they have found the cure?

These claims are however at odds with what the prestigious National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the CDC in the US have stated on their updated websites. They’re very clear that there are no proven effective or curative treatments for ME. With regards to harm and damage, besides numerous patient surveys showing that indeed patients are being worsened by CBT/GET, there are only a few studies that actually reported these troubling aspects of CBT/GET. However, there are definitely indirect consequences like increased disability benefits, reduced working hours, low adherence to the treatment and more drop outs in the treatment arm than in the control group.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for CBT and GET from its website. The 2015 NIH Pathways to Prevention report has suggested that the Oxford definition should be retired stating that it could “impair progress and cause harm” as it’s only based on having 6 months of chronic fatigue and PEM is not a requirement or required symptom.

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) issued an Addendum to its 2014 ME/CFS evidence review which downgraded the conclusions on the effectiveness of CBT and GET.

They state that using the Oxford case definition results in a high risk of including patients who may have an alternate fatiguing illness or whose illness resolves itself spontaneously with time. Furthermore, blatantly missing from this body of literature are trials evaluating the effectiveness of interventions in the treatment of individuals who meet the case definitions for ME or ME/CFS.

This means that these leading institutes have distanced themselves from many behavioral studies including a ‘5 million pound’ worth controversial clinical trial called the PACE-trial which was based on the Oxford criteria. Ouch!

“Patients diagnosed using other criteria may experience different effects.”

The Cochrane review has been hopping along with the “yay CBT and GET for everyone” bunny trail. However in their amended version of the review, ‘Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome,’ it now places more emphasis on the limited applicability of the evidence to definitions of ME and CFS used in the included studies. This limited applicability also extends to the long-term effects of exercise on “symptoms of fatigue”, and also acknowledges the limitations of the evidence about harm that may occur. It’s the first time that they have acknowledged that using stricter ME criteria will affect the outcome in regards to harm and debilitation.

“All studies were conducted with outpatients diagnosed with the 1994 criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Oxford criteria, or both. Patients diagnosed using other criteria may experience different effects.”

In the Netherlands we had the Dutch Health Council that based the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2015 report somewhat on the developments of the whole situation in the United States, but in the end, as there were quite a few CBT proponents, the Dutch Health Council’s advice is much more lenient towards CBT/GET than what the CDC, NIH and the AHRQ say. Other than some good points in the Dutch Health Council publication, the information in the Netherlands about ME is still inaccurate, both in guidelines and on websites like the one from the NKCV.

In the Netherlands ME is pretty much synonymous for chronic fatigue and a cluster of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS). The hallmark symptom PEM is not required for diagnosis or not even mentioned at all. The Netherlands still recommends harmful treatments to patients. It has the potential to unknowingly cause iatrogenic harm, both physically and mentally.

Communication.

It creates a very difficult situation for both patients and physicians. Apart from the newcomers, patients that have been around for a while are often aware of the reality around these treatments. For us patients it’s easy to keep up with the latest developments in the science relating to ME. We only need to focus on just one disease at the time. The internet has also led to the development of a more informed, educated patient, who is willing to play an active role in medical decisions.

Clinicians suddenly have to deal with a patient who has predetermined notions. This includes information that are at times unfamiliar to the physician or at odds with the physician’s medical approach like what’s happening with CBT/GET. I guess we’ve moved from trusting a doctor blindly to trusting a doctor who is well-informed.

Not all the information that patients bring to the table might be of value but some will be. This can of course cause quite a bit of friction. It might add to the sentiment that a physician considers a patient “difficult”. Especially if a patient rejects “proven” treatments like CBT/GET and insists on off label “alternative” therapies.

Not all the information that patients bring to the table might be of value but some will be. This can of course cause quite a bit of friction. It might add to the sentiment that a physician considers a patient “difficult”. Especially if a patient rejects “proven” treatments like CBT/GET and insists on off label “alternative” therapies.

I changed GPs 3 times because I just couldn’t find one that was knowledgeable in regards to my disease. The first one in Amsterdam would just order a few tests and tell me to come back in a few months to do another few tests. The second one as noted offered me CBT/GET and the last one wanted me out of the office before I even came in. Some people might refer to me switching doctors as shopping. Some feel this is purely because of getting secondary gains from having another doctor.

A study from Japan by Natsuko Nojima from Osaka University concluded otherwise:

“The seemingly excessive treatment behavior called ‘doctor shopping’ is actually linked to doctors’ ignorance, suspicion and incomprehension of diseases without a biomarker rather than the desire of the patient to dispel an ‘inappropriate’ label of laziness and mental illness”

“Furthermore, when considering this role of the independent-patient, it should be borne in mind that patients do not act in pursuit of secondary gain. As ME/CFS is hardly considered a “disease” even after obtaining a definitive diagnosis, under the current situation where appropriate care is not forthcoming for the symptoms, it is presumed that the definitive diagnosis of ME/CFS is not effective enough for social approval of the illness.”

“If doctors are not provided with adequate information about a disease, can you really blame them?”

The fact that my GPs weren’t really connecting with me made me feel like I wasn’t heard but most of all, like the Japanese study also states, I simply didn’t receive the care that was clearly needed. While it is of course of the utmost importance that my doctor is also knowledgeable about my disease, the connection with the caregiver is at times more important than the need to obtain treatment itself. This is something, due to a lack of knowledge, that is often missing.

While I’m not a fan of referring to MUS or a functional disorder in regards to ME, a study by Kromme et al. found that when confronted with medically explained symptoms (MES) or medically unexplained symptoms (MUS), internists seemed more distant and controlling, and tended to draw on their own medical expertise. It clearly creates a distance between the patient and the clinician and that distance becomes counterproductive. Yet again if they are not provided with adequate information about a disease, can you really blame them?

I actually love you!

ME patients are often described as difficult and hateful. We’ve seen social science researchers complain in the media about personal attacks. Now besides the fact that I can imagine it’s not easy to get continuous criticism on your work, we are talking about valid criticism on flawed science and the scientist, not the person. There is a clear difference. On top of that these claims of harassment were considered grossly exaggerated in a court of law regarding the PACE-trial, it does feed on a view that certain clinicians have of ME patients. However has this been something exclusively seen with ME patients?

In an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association dating back to 1965, rheumatologist George Elrich describes the situation with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients.

He treated a patient whom he later sent to a so-called “very” skilled surgeon and concluded that when she didn’t respond well enough to the surgery and treatment, there was no longer an organic basis for her suffering. He describes how she was still tyrannizing her husband who had become her virtual slave.

“The Hateful Patient’ is not a patient who hates you – it is a patient that you hate.”

“Beware of the hateful patient.”

From what I understand, these surgeries were woefully inadequate, so the lady was most probably still very disabled and in agonising pain. Yet the fact that she therefore still needed help from her husband was mostly considered her own fault and not the treatment or the surgery’s. This is a prime example of unfounded patient blaming in full force.

He then explains that doctors often referred patients to him:

“The attending physicians often begged me to take over the total treatment; they pleaded inexperience with chrysotherapy or other transparent excuses. In reality, they often found the patients unpleasant or frustrating to treat. Someone once told me, not altogether facetiously, that if a patient who appeared to have rheumatoid arthritis was not hateful, the diagnosis was suspect.”

I have a few friends who have RA, but I haven’t really noticed that they were especially hateful or tyrannizing to anyone. It rather seems that doctors were extremely uncomfortable with the fact that they didn’t really know how to treat and cope with these patients who were clearly in pain and distress. It might have been easier for these doctors to blame the patients and portray them as hateful than to blame themselves for any shortcomings in providing adequate treatment.

The fact is that actually nobody was at fault here. The knowledge simply wasn’t there yet but for some reason that seems to be a difficult fact to accept. RA patients were unjustly labeled as unpleasant and hateful when there was really nothing these patients did wrong. It sadly is very reminiscent of how ME patients are similarly portrayed in 2020.

Miscommunication.

As a result of this type of miscommunication and lack of knowledge many patients start avoiding care all together. In a study by Timbol et al. by researchers from Georgetown University Medical Center the perceptions of ME patients’ care in a hospital’s emergency department (ED) were examined. From the 282 participants, 41 percent of respondents did not go to the ED when ill because they felt “nothing could be done” or they would not be taken seriously. Only 59 percent of the patients had gone to an ED. In this group, 42 percent were dismissed as having psychosomatic complaints.

A similar problem was seen in a report from Norway by Angelsen et al. of very severe ME patients called “Mapping the Situation of the Sickest ME Patients”.

A similar problem was seen in a report from Norway by Angelsen et al. of very severe ME patients called “Mapping the Situation of the Sickest ME Patients”.

The report states, among other things, that only one in three severe or very severe ME sufferers felt that they were believed by health professionals. And only 10 percent of respondents with severe ME received adequate health care, compared to 20 percent of those with very severe ME.

Many people do not get home visits from health care professionals when they need it. A large proportion are in fact without health care.

Two out of three with severe or very severe ME have experienced contact with one or more professionals in the healthcare system which turned out to be so difficult that they do not dare or wish to have further contact with any of them.

We recently lost someone here in the Dutch community who told me I could use his case as an example. We were both 41 years of age. Both suffering from a severe form of ME. Living in a darkened room with earplugs and construction workers headphones. We both had the same type and severity of symptoms with orthostatic intolerance (OI), cognitive impairment, light and noise sensitivity, food intolerances with gastrointestinal complaints and of course severe PEM.

“Because of the lack of knowledge many patients start avoiding care all together.”

Unlike me he also had a psychiatric disorder on top of his ME and while without this disorder, it’s already hard to get proper (bio)care for ME, due to his mental health all of his physical complaints were considered to be of a psychogenic nature. It resulted in him being left completely untreated and thus his rapid deterioration.

While I don’t especially love the website of the CDC even they recommend testing and treatment for OI, both non and pharmaceutical interventions. OI is considered one of the most treatable symptoms of this disease. He however was never tested nor treated.

It took a lot of effort and persuading for him to finally and temporarily receive B12 injections to see if it would make a difference and that’s all he got for his ME. Vitamins!!!

No bio?

It’s of course confusing when Dutch guidelines recommend CBT and GET as “safe” and then recommend against pharmacological interventions. While this of course seems to fit within the principle of “primum non nocere”, the guidelines are from 7 years ago. The only thing his GP decided to arrange was a trip to a MUS clinic. The trip alone would have been detrimental to his health considering the state he was in, causing him to deteriorate even further. On top of that the MUS clinic treatments are really not suitable for severe ME patients.

A few months after our last email exchange I heard that he had passed away. It breaks my heart to know that he died without the treatment and care he should have had and deserved.

Can I blame his GP for the lack of medical care from her side? Not really. With the lack of proper guidelines for ME she probably became uncertain on how to deal with a severe ME patient and as a result, sent him off to an MUS clinic as they’re considered experts in “chronic fatigue”. She acted much like the internists who created a distance between them and their patients once there wasn’t a set plan to be followed. Doctors panic and get blocked.

None of the Dutch MUS guidelines are accorded by any of the patient organizations as they don’t fit the disease mechanism and/or the clinical picture of ME. Go figure. It is a huge problem. Considering his tragic death, this urgently needs to be changed. The lack of care or unwitting medical neglect is sadly rather the norm than the exception. It causes us ME patients a great deal of unnecessary harm. It needlessly puts doctors on the spot with only inadequate information available when they are simply trying their best to help.

Science, the CDC and the IOM report are clear. ME is not a psychological disorder. This is not only because of the type of abnormalities found throughout biomedical research but studies also have shown that the pattern of the disease matches that of other chronic illnesses. About 40% of the patient community suffers from secondary depression and anxiety problems versus 60% who do not. This is similar to what is seen in other chronic conditions like multiple sclerosis, RA or diabetes 1.

“A dualistic approach of ME by dropping the bio and solely focusing on the psychosocial.”

The situation with him was first of all worrying because it paints a very bleak picture of how patients with a mental health condition are being treated as a whole. It paints an even bleaker picture of an ME patient with additional mental health problems who was simply disbelieved that he could also be suffering from a physical condition because the physical condition is out of ignorance, often not recognized as such.

Psychiatrist Dr. George L. Engel, the developer of the biopsychosocial model, must be rolling over in his grave in utter shame by the dualistic approach of ME by dropping the bio and solely focusing on the psychosocial. A harmful dogmatic psychosocial model where the treatment can even result in forced institutionalization. For example in Denmark, and the UK we see similar things happening, not to mention in the Netherlands.

This can’t be how health care was intended to be, yet we’ve seen this happening with so many diseases throughout history. Why don’t we seem to learn from our mistakes? Can we please make this stop?!?

Improving.

So what can be done to improve the communication between doctors and patients? Reading through some of the literature of the “difficult patient” I also read a lot about empathy. You know empathy may lead to better insight as to why a patient is really in distress. Like with RA, it’s clearly unhelpful to simply label a ME patient as “difficult”. Are they really or is it (partly) because of the clinician who finds the situation difficult instead of the patient itself?

If both recognize that there are limits to the overall knowledge, could it possibly lead to a kind of “partnership” between the doctor and the patient exploring alternative options?

Professor of primary care Trisha Greenhalgh:

Doctor: Don’t confuse your Google search with my 6y at medical school.

Patient: Don’t confuse the 1-hour lecture you had on my condition with my 20y of living with it.

— Trisha Greenhalgh #IStandWithUkraine 🇺🇦 (@trishgreenhalgh) May 26, 2018

I don’t have a medical degree. Nor do I have a scientific background but with my knowledge of my body as both a former professional dancer and being a 13 year experienced expert with the disease, it does count for something as well. With the medical knowledge of a doctor we could come a long way. When a doctor is willing to exchange ideas, even ask for the opinion of the patients and really listens, we patients trust more in the relationship, which subsequently improves significantly.

Now empathy is important but if the knowledge is still lacking, it will continue to lead to miscommunication in the doctor’s office. At the moment, doctors in the Netherlands mostly rely on the information that is disseminated by the MUS proponents, but for us patients this is of very little use. It’s sadly part of the problem instead of the solution. There is definitely more suitable information available.

Here are some great examples of what could be explored to increase your knowledge about ME:

Dr Nina Muirhead, a dermatologist at the Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust herself became ill with ME after developing acute Epstein Barr Virus Glandular Fever. She first of all didn’t know or understand much about ME but more importantly it was an illness she didn’t really believe in.

Prior to her becoming ill, she had a vague notion that ME was an illness related to deconditioning, which she clearly found out to be incorrect. The NICE guidelines had perpetuated her misunderstanding of ME by recommending CBT and GET. This pretty much paints the picture of how, based on the Dutch guidelines, doctors in the Netherlands also approach this disease.

The CMRC Medical Education Group which is led by Dr Nina Muirhead has launched in partnership with Study PRN an online course for medical professionals about ME.

You’ll get to read case studies of patients who may or may not display symptoms of ME, decide what those symptoms might be indicating, what diagnosis, management advice and/or medications to consider. It will count towards the continuation of professional development and result in a certificate.

You can find out more about the course here: https://www.studyprn.com/p/chronic-fatigue-syndrome

The Dutch ME/CFS association just sent out copies of the International Consensus Criteria (ICC) including its primer for both adults and children to many GPs throughout the Netherlands. You can find both the criteria and the primers here:

ICC: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x

For those who are short on time. A basic summary has been published by the U.S. ME/CFS Clinician Coalition on how to diagnose and treat ME. In the references you’ll find some additional useful resources. You can find out more here: https://bit.ly/3e8MKDp

For a CBT (with GET), replacement pacing is the only way to go. Consider reading more about the Energy Envelope Theory: https://www.me-pedia.org/wiki/Energy_Envelope_Theory

Update: Make sure to read the new NICE guideline 2021.

https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-me-cfs-guideline-outlines-steps-for-better-diagnosis-and-management

“The secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient”

– Francis W. Peabody, MD, Harvard Medical School

I sincerely hope that with describing the current situation from my perspective as a patient, it has given those who managed to get to the end of this very lengthy blog a better insight into why the current way of treating patients has in my opinion often been ineffective and/or even counterproductive.

The only way forward would be in validating the patient’s experience by really understanding the disease through education which will then increase the understanding of the patient on the whole. This will prove to be more satisfying to both parties and it will thus diminish negative sentiments between the patient and the physician. There will be less of a risk that the patient will become a “hateful patient” and that hopefully will contribute to an encounter that will be clear of any mutually perceived fear.

Thank you for reading!

Anil

Editor: Russel Mohan