Last year I turned forty. For most people, such an occasion is cause for reflection. This is especially true when severe illness has formed a major part of life. Having been seriously ill with ME since the age of twelve, birthdays such as this are some of the only ordinary landmarks I’ve passed in my life. The numbers go up with alarming rapidity, but the life events which normally accompany them remain absent.

One faces the scarcely comprehensible imbalance of glimpsing middle age while still waiting to experience teenage milestones. My age says that I should be established in a career, with my own home, a partner and children. (Or at least some combination of the above.) The reality is that my world stopped turning in any normal way when I was still a child.

Major birthdays are a jolting reminder of just how much time has passed. I clearly remember celebrating my parents’ 40th birthdays with them. I am now the age that they were when I fell ill. (A particularly difficult fact to get my head round.) The babies and children of my early illness are now parents themselves. I have been ill for an entire generation

Forty: what if I was still ill when I was forty?

As a teenager, terrified about my illness and what the future might hold, I remember trying to picture what life would be like if I never got better. I stretched my imagination as far as I could, like a fragile rubber band, until I reached an age that was at the outer limits of what I could comprehend. Forty: what if I was still ill when I was forty? To my teenage mind, contemplating a time so distant felt like gazing into space and trying to grasp the distances contained there. Forty was at once terrifying and utterly impossible to imagine. It chilled me, the thought that I might still be suffering so far into the future. That I might still be living in my parents’ home, still dependent on full-time care, still measuring each day into tiny portions of doing.

Last March, that once distant fear became a reality. I reached forty, fundamentally still living the same restricted life that I knew as a teenager. It would be wrong to say that nothing has changed. I’ve made progress, much of it significant. My life is fuller and far richer than it was back then. I have grown as a person and I have known some special experiences. But this does not represent the growth and potential that it is reasonable to expect from life. If I have found promise, it is because I’ve squeezed it from the seemingly impossible.

Most situations in life can be viewed from more than one angle, and this is perhaps most true when loss and bitter disappointment are present. I can look one way and see the wreckage of what I might have wished for from life. I can see the agony, the pointless suffering, the absolute devastation. I can see the denial of my illness and the medical abuse I’ve suffered; the fact that the course of my illness would have been so different had I been treated correctly. I can see the ongoing daily suffering, the restrictions so great that the spirit weeps. I can see the prospect of life forever being experienced at arm’s length.

My teenage self was both right and wrong to fear my life as it is today

But I can adjust my angle of vision and see that my forty years have been lived to the best of my ability. That I have been loved and that I have known joy. That in coming back from some of the darkest experiences one can know, I have learned to treasure what is truly important. My life may have been very different to the one I would have chosen, but it has still been a life of purpose and happiness. I am grateful for every day that I have been given, particularly when I think of friends who have not lived to see their 40th birthdays.

These two perspectives sit side by side, neither one cancelling out the other. When writing a piece like this, it is tempting to settle on one viewpoint as more deserving of the last word: to end on a decisive note of either optimism or sorrow. In reality that is impossible. My life can be viewed from multiple angles, and that ability to shift perspective is what gives us strength as humans. We need to be able to summon hope, to find contentment in circumstances that fall far short of our expectations, to take pleasure in an imperfect world. But we also need to be able to wail and grieve, to express anger and demand better. Sanity is found both in recognising the good and in being honest about all that is wrong.

My teenage self was both right and wrong to fear my life as it is today. Right because it is an injustice that should never have happened, and a waste of so much potential. Wrong because, in spite of it all, life is still worth living.

Naomi Whittingham

Footnote: It is important to say that this is my personal perspective and will not be representative of all with severe ME. A supportive, loving family and improvements in my condition have allowed me to find meaning in my life, despite its huge limitations. In this respect, I am one of the lucky ones. Others are not so fortunate and face a relentless battle simply to exist. Those living with this illness and struggling to see any purpose are not lacking strength – on the contrary, they are the strongest of all.

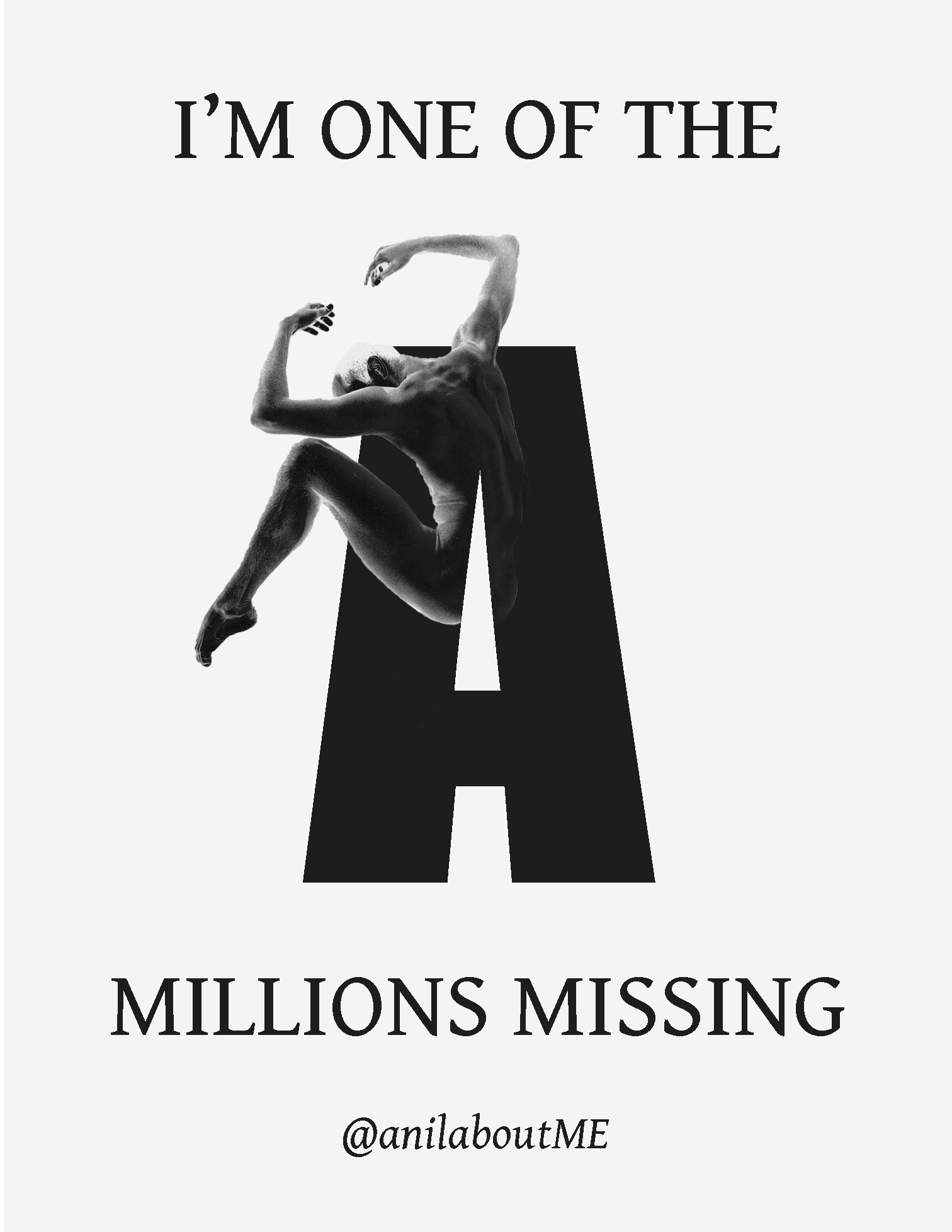

Note by Anil:

Please watch the documentary Voices of the Shadows featuring Naomi Whittingham. You can click on the right top corner of the video “rent $3.00” and subsequently enter the promo-code “VOICES” to watch the movie for free. This film is not suitable for children and young people with ME who may be distressed by viewing it. You can read more about the movie by clicking here.